The Evolution of Fashion Through Human Behavior

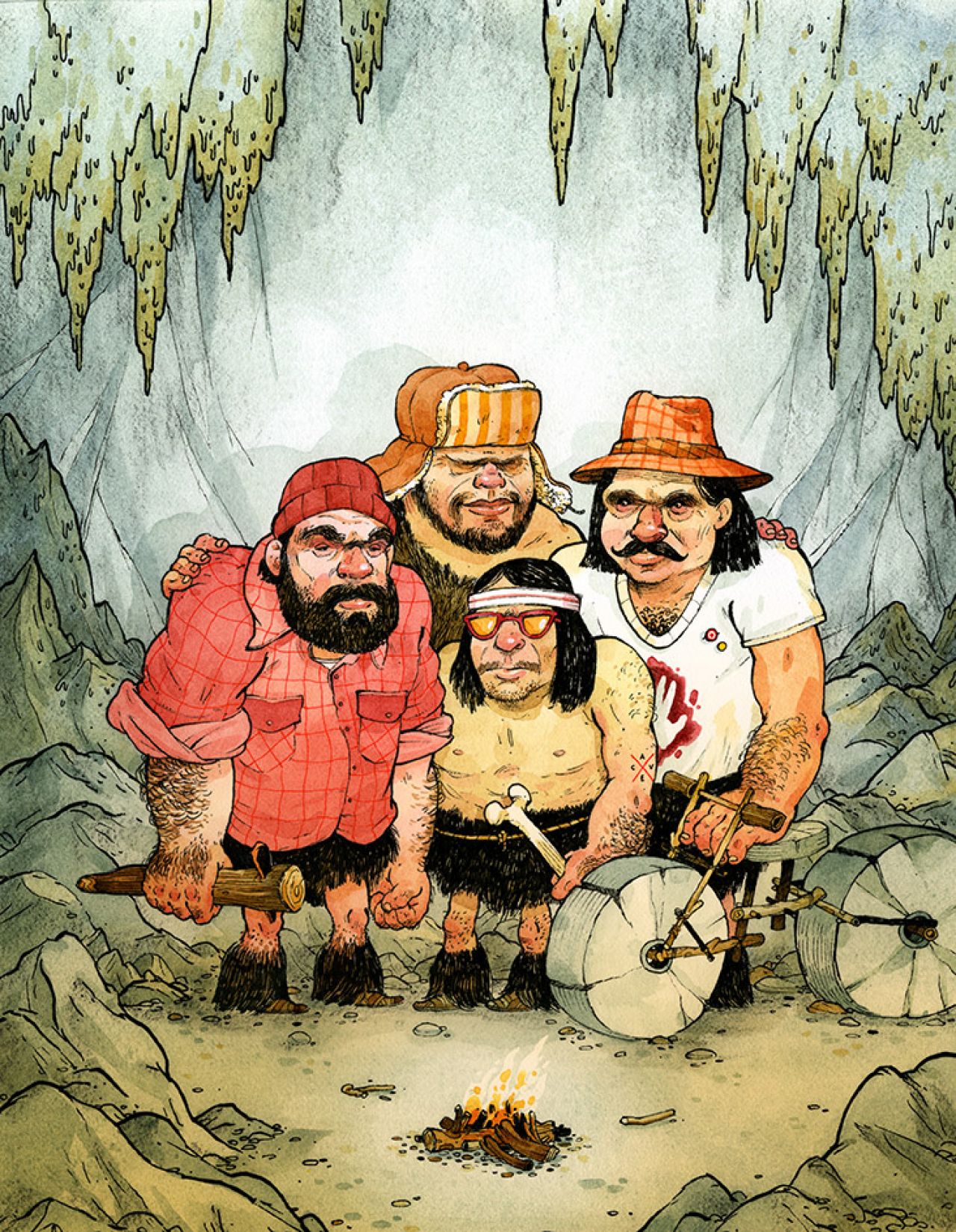

P icture ane of those ascent-of-man charts that depict a progression of profiles, from an ape walking on all fours to a slumped hominid to a modern human standing erect. What's missing? The modern human is naked. No accessories!

We may not discover a affiliate on fashion in science textbooks but ornamentation and tailoring accept played feature roles in our success as a species. On the prehistoric catwalks we creamed the Neanderthal competition on both functionality and style and went on to become the dominant hominid in virtually every climate zone on world.

As I discovered through a host of interviews with paleontologists, anthropologists, evolutionary psychologists, and fashion historians, dress don't just make the man—they make us human. Apparel and body ornament evolved in a suite of homo communication tools and behaviors that have shaped the runway of homo development and culture.

Dress don't only make the human—they brand us human.

Fashion has been as "crucial to the emergence of the mod man every bit music and trip the light fantastic toe, art and humor, and linguistic communication," says evolutionary psychologist Geoffrey Miller, an associate professor of psychology at the University of New Mexico. "It's a legitimate part of human nature."

That'south hardly news to the well-dressed man and adult female. Still, putting way and science in the same judgement can seem a little strange. So, to reassure you that the pride and excitement you feel when yous put on an Armani suit or a pair of Manolo Blahniks is emotionally legit, allow's plow back to our evolutionary past. The dawn of clothes reveals that we were born to strut.

Southince at that place are no prehistoric

scraps of article of clothing lying effectually, scientists have had to get artistic in their

quest to pin downwardly the point at which humans started wearing duds. They began to

scratch their heads and realized that one approach might exist an analysis of

lice. Trunk lice, adapted to clothing, seemed to be key.

Indeed, a recent analysis of lice

Deoxyribonucleic acid by David Reed, acquaintance curator of mammals at the Florida Museum of

Natural History, establish that humans probably wore their get-go clothing, torso

lice included, about 170,000 years ago, some 830,000 years after our ancestors

lost their body hair.

Why we shed our body hair is

debatable. One leading theory is that losing it allowed us to shed pre-clothing

lice and other blood-sucking, deadly parasites, which infested our ancestral

fur. Another theory is that when nosotros emerged from the forest to the blazing

savannah, nosotros needed to cool our body temperature, and exposed peel sweats.

In any effect, says Ian Gilligan, a

bioanthropologist at the Australian National University, who is an adept in

the prehistoric development of clothing, the engagement of 170,000 years ago makes

sense, as it roughly coincides with the penultimate ice age, 180,000 years ago.

"Humans only began to wear clothing when they needed to proceed warm," he says. Gilligan says that a few degrees beneath zero Celsius represents "the limit of human cold tolerance without protection."

Even before the widespread advent

of wearing apparel to keep warm, early humans decorated their bodies. "It is highly

probable that we were adorning ourselves with torso paints, found materials, and

animal skins for the entire history of our species," says Nina Jablonski, a

paleobiologist at Pennsylvania State University, and the author of Skin: A Natural History. "Beautification

creates a visual shorthand that tells others instantly who nosotros are, who we want

to associate with, and who we wish to be," she says.

In

the fossil tape, ornamentation began showing up roughly 75,000 years agone.

Archeologists believe ostrich shells were used as beads and red ochre was

probably used as body pigment. Past the fourth dimension of the Upper Paleolithic in Europe, 35,000

years ago, prove of bone needles suggests that people were making sophisticated,

tailored clothing with multiple layers that shielded them from the cold.

Neanderthals' lack of sophisticated clothing contributed to their extinction.

Neanderthal vesture, in

comparison, was shoddy. Gilligan argues that Neanderthals' lack of sophisticated

clothing contributed to their extinction, which happened during some sudden,

severe cold snaps around 40,000 to 35,000 years ago. "Only modern humans

equipped with tailored vesture managed to migrate into those most thermally

challenging places, and but after they had invented eyed needles and other

technologies for manufacturing sophisticated, multi-layered habiliment—including

the world'southward first underwear," Gilligan says.

During the Upper Paleolithic, our ancestors

poured huge amounts of time into ornamenting their garments. In Sungir, an

archaeological site due east of Moscow from 26,000 years ago, effectually 12,000 pierced mammoth ivory beads

were found in the graves of 3 individuals—a male person adult and two children—that

had been sewn onto manufactures of their vesture. Archeologists estimated that it

would have taken an hour to make each bead with stone tools—thousands

of hours of work. "It's non simply a little ornamentation," says anthropologist

Robert Boyd, coauthor ofNot By

Genes Lonely: How Culture Transformed Human Evolution. "Information technology's a

big investment. This is a display of wealth."

And so, you lot can cease fretting virtually

being a dress horse; showing off in your finest threads is not fiddling only an

innate part of homo nature. Polly Wiessner, an anthropologist and professor at

the Academy of Utah, has studied how hunter-gatherer tribes in the Kalahari

Desert utilise body beautification to enhance personal identity and social

interaction. "The fact that all humans feel well when they know they look well,

and experience desperately when they expect poorly, suggests that the quest to look well by

socially stipulated standards is a biologically-based predisposition," she

says.

Having a biologically based manner sense, you might say, is not limited to humans. Other animals are into adornment. Decorator venereal attach seaweed, sponges, and anemones onto their shells for camouflage. Bowerbirds decorate courtship areas with artful piles of flowers, irised shells, $.25 of colorful fungus, and other objects from the forest floor. Almost famously, of course, the male peacock fans out his magnificent tail feathers to attract female mates. And it'south truthful, evolutionary biologists tell us, when we dress to print, nosotros're non and so different from the proud peacock or dancing bowerbird.

But virtually animal display tactics

serve basic survival and mating purposes. We tin can use manner to express a broad

range of human emotion and intention, thanks to the organ below our hats.

Fashion tin can exist seen equally a form of symbolic communication ("a simplifying

stand-in for something complex," says primatologist Robert Sapolsky), standard operating procedure of the evolved human being brain.

Paleontologist Ian Tattersall, author of Becoming

Human: Evolution and Human Uniqueness , says mode is an example of our

unique cognitive ability to dispense meaning and data. "Trunk

ornament and clothing, and the significance that we impute to them, are

intimately tied into the kind of animate being that we are," Tattersall says.

Wiessner goes further. Echoing the groundbreaking

work of developmental psychologist Michael Tomasello, who

claims that humans alone are able to sense the intentions of one another, she

says that because we can "read the minds of others … we can attach a whole

range of meaning to certain bodily decorations that animals can't."

"Fashion is near showing that you lot accept inventiveness or taste that others don't have," Miller says.

To evolutionary psychologist

Miller, expressing and understanding a whole range of meanings is a trait

bestowed on u.s. past development, equally a means to attract sexual partners. In his 2001

book, The Mating Heed, Miller argues

that "our minds evolved not just every bit survival machines, only as courtship

machines." He writes that human traits that seem to have no directly survival

benefits—"humour, storytelling, gossip, art, music, self-consciousness, ornate

linguistic communication, imaginative ideologies"—evolved to entice and entertain sexual

partners. Information technology's a provocative thesis that has its critics, who maintain that

Miller overplays the role of sexual pick among the circuitous biological and

cultural forces that have molded united states of america as a species. Nonetheless it'south a view that

underscores the importance of fashion in expressing a richness of personal and

social traits.

Fashion "is all most signaling and

display, it'south about showing that you've got some resources or inventiveness or

taste that others don't have," Miller says. "You gain higher status in your

group and among your rivals, and that status translates into better access to

food and shelter, friend networks and social back up."

Marking Twain, known for his natty white suits, once opined, "Naked people have trivial or no influence in society." The great wit was more profound than he may have known. "If other people favor you lot, you really accept an advantage in human society," says anthropologist Wiessner. "If you can nowadays yourself positively and look attractive—even if you're not peculiarly attractive—it tin evidence wealth, it tin can show social connections. You lot're more than likely to get people to invest in y'all."

Today, in a consumer order with countless

fashion choices, we have more ability than ever to arts and crafts our own identities and

signal the groups and subcultures with which we acquaintance. "With mass-produced

fashion," Miller says, "yous're showing off not what kind of way you lot can

afford, merely what kind of person you lot are, what your personal traits are, what

your interests and values are. The divergence between somebody wearing a black,

$20 heavy metal T-shirt and another wearing a $20 polo shirt is not wealth—it's

certain subculture."

Valerie Steele, director and chief curator

of the Museum at the Fashion Establish of Technology in New York, agrees that contemporary

style allows people to clothing what they desire and not be fixed in identify in a

social lodge. People of all means, for instance, she says, "wear blue jeans."

Steele also reminds u.s. that style allows us to enhance our physical

characteristics. "Clothing tin make the body do things that it wouldn't be able

to do otherwise—like my eyeglasses can brand me encounter better, my shoes can protect

my feet," she says.

And engineering makes human being identity

even more fluid. "The whole idea of the cyborg is related to fashion," Steele says. After all, she adds, prosthetics

tin be seen "as another kind of accessory that yous put on your body to enable

y'all to do more things." Soon enough, eyeglasses will double every bit wearable

computers. Currently a new moving ridge of designers is employing computer-aided design

to create 3D-printed garments for private customers, based on a body scan. And

scientists are creating materials, with microminiaturization, that tin change

patterns or colors at the whim or mood of the wearer.

As

ever, fashion is tapping into our innate ability to express who and what we

desire to be, opening new doors to self-expression and social influence. Look

again at our chart of the ascent of homo. This fourth dimension, imagine Human sapiens properly clothed and

accessorized. How could it be otherwise? Without fashion, nosotros would not be homo

at all.

Jeanne Carstensen is a author in

San Francisco. Her work has appeared in the New

York Times, Salon, Modern Farmer and other publications.

0 Response to "The Evolution of Fashion Through Human Behavior"

Post a Comment